Faisalabad ( Lyallpur historical facts)

Lyallpur: Historical facts (Part 1)

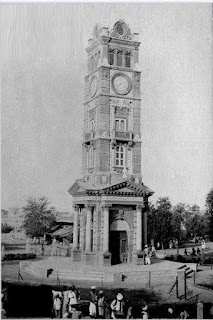

A city which owes its development to British Empire can still see some white-robed missionaries educating generations. The confluence of eight lines, a reminder of Union Jack, drawn by Captain Young is still registered as Clock Tower and the spacious verandahs of Chenab Club where British officers relaxed still smell of Raj.

In later part of 19th Century, as British decided to develop Punjab, they resorted to irrigation system and land allotments. The gracious allocation did consider the allegiance with Raj since those who stood next to British during 1857 war, had their lands next to canals. Chenab Colony was the first name given to this settlement of Baar.

It was during this allotment that family of Master Sunder Singh Lyallpuri migrated from Jalandhar and made Lyallpuri, a part of their name. Master Sunder Singh had not only taught Sir Sikandr Hayat and Giyani Kartar Singh but was universally referred to as Master. A gifted visionary of his time, he was credited for his nationalist movement, Punjabi newspaper and a chain of public schools in remote areas of Punjab. The building of Lyallpur Sangh Sabha, near the canal was converted by him into Khalsa High School. The school eventually grew into a college and the college became an icon of Lyallpur.

After the Jallian wala Bagh incident, police arrested Master Sunder Singh and charged him for murder. Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya, the brilliant educationist and lawyer, fought his case and managed to scrap the sentence to eighteen months imprisonment at Andaman Nicobar Islands, though the fine cost him his ancestral land.

On release, he started Akali, the best-selling Punjabi daily of its time. Akali had a nationalist tone which instantly grew loud enough for the British to notice and subsequently silence it. Master Sunder was arrested and the paper was shut down for a brief period. Soon the Urdu version was also published and on Pandit Malviya’s advice, Master Sunder Singh started “Hindustan Times”, the English newspaper. Initially the financial aid from Sikhs of America provided for the paper but due to frequent official clamp downs and financial issues, it could not continue. Pandit Malviya ran the paper for a while but soon it was sold to Ghanshyam Das Birla. A congressman to the core of his heart, Master wore khaddar for most of his life, believed in complete autonomy and equal rights for minorities.

Before Partition, the city had a healthy mix of Sikh Jaats, Muslim Sheikhs, Hindu businessmen and a very limited Anglo-Indian community. This composition also shaped the economical outlook of the city. Jaats held the agrarian side, Sheikhs and the Hindus did the industry and Anglo-Indian community was busy in keeping the stiff upper lip traditions of Raj through clubs, schools and offices. While Ganesh Mill and Khushi Ram Behari Lal Mill (now known as Lal Mill) provided a lifestyle to the city and kept the city on toes during day, evenings would see Ganda Singh, a local landlord, ride his famous Tonga majestically.

The city was famous because of the eight bazaars that led to eight different locations. The bazaars initiated from Clock Tower and going outward they made smaller rings and connected the inner side of these bazaars in growing circles.

There was a time when these connecting streets were famous for gifted people instead of seedy retail shops. In one of the lanes, Fateh Ali Khan and his brothers practiced their daily regimen of Riaz, the success stories of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Rahat Fateh Ali Khan were a generation away. Few houses down the road, at Barrister Khajan Singh’s Place, his daughter Teji, a lean girl with sharp features performed Keertan alongside her mother. Teji soon graduated from hymns to Shakespeare and was teaching at Lahore when she met Harivanshrai, a poet who taught at Aligarh. They married in 1941 and were blessed with a son, next year. India, those days, beamed with revolution so Teji and Harivanshrai named their son “Inqilaab”. Samatranandan Pant, a poet friend convinced the parents to change the name. He suggested something more meaningful, ”Amitabh Bachan”.

Two phenomenal buildings stood on both ends of Thandi Sarak, District Jail and Agriculture College on one end and Chenab Club on the other end. Outside the city, fame had come to Bhagat Singh and the son of Dewan Basheswarnath, a police sub inspector.

And after 1947, it was never the same. Many prosperous families migrated and surnames like Khanna, Chawala and Maggoo were lost in the junkyard of memory, much like the disused articles in attic.

With new found freedom, Lyallpur woke up to its commercial side and within years, the Industrial boom set the new socio-cultural tone. The vacuum created by migration was filled by a relatively ambitious class.

The first blow to its liberal cosmos came, when a circular passage, which ran though inner sides of eight bazaars, was blocked. A tent was pitched, initially for prayers, and after sometime, the foundation stone of the mosque was laid. This was followed by the house of Imam and finally a madressah raised its head. Anyone who objected this blockade was silenced with threats of heresy. Naively, every encroachment in the land of pure starts with the mosque. Men who block the passages in the name of religion never realise that, literally, religion means passage. Taking the lead, Khalsa College was christened to Municipal College and Company Bagh was nationalised to Bagh-e-Jinnah.

The city initially responded to the social cause of Peoples Party, but soon realised the hoax slogans of subsistence. Its dynamic leader furnished his pan-Islamic dream at the cost of a legacy when he named the city after the Saudi monarch. The citizens of Faisalabad, unfortunately, were not as resilient as those of Jacobabad who took it to streets when the name-change was proposed. Disillusioned and exhausted, the city never looked left after Bhutto. Though the names were changed in the revenue record but for Dadi, Faisalabad, Municipal College and Bagh-e-Jinnah remained Lyallpur, Khalsa College and Company Bagh.

While Indulgences (certificates of Pardon) meant money could wash away the catholic sins of 17th century Europe, donating to mosques translated to compensation for Islamic sins in early 80′s Faisalabad. A dictator had taken over the country and chose to draw legality from religion. During all those years, donating hefty amounts and collecting sacrificial hides became a virtue and doing it publicly secured a seat in the parliament as well. Other cities survived this onslaught because of their rich history but having grown from a market, Faisalabad could quite not resist. The monsoon of jihad catalyzed the wild growth of madressahs and the Rayals that financed this venture, brought along the hard-line belief. The ship had started to sink.

Firstly, the dialogue vanished, then the study circles and literary traditions and gradually the city was transformed. The question of religion, now, is synonym to question of violence. The city lives with no room for dialogue and no space for reason. Any debate on this issue starts up with mild mannerism but, in a subtle way, tones get harsher, words start offending and temples begin to pulsate. Faisalabad may not wear black in mourning of Muharram but turns so green in Rabiul Awal festivity that it fails to spot the oozing blood.

While the rich don’t care and the poor don’t bother, the middle class, a universal safeguard for any social tendency, is too absorbed in Metros and coffee shops to check the diminishing tolerance. Different mosques of different sects dot each corner and are busy turning the inquisitive minds into hobbits of their respective belief. The small thinking fraction is either too indifferent or too preoccupied to notice.

The city, no more belongs to calm people of art and craft but rather reminds one of the Bible belt where religion and business have converging axis. Regardless of blasts that rip through the country, Faisalabad remains unaffected because the clergy and the trader are friends from ages. Exploiting the repentance of rich in the name of Shariah, even today, any religious organisation can collect funds to their hearts content, if they walk in any of the markets.

The towns of Gobindpura and Harcharanpura mourn their past. There was a time when an open space was left for community gatherings between the two bazaars. A Gurudwara stood between Katcheri bazaar and Rail Bazaar while a temple watched over the passage between Rail Bazar and Karkhana Bazaar. The street to temple is taken over by the hosiery retailers and a school houses the Gurudwara. Gurumukhi script on the front has been washed away with rains but the Seva Karai plaques are still visible. Black boards have been erected in yellow walls of Gurudwara. The house of Guru is now the house of learning.

While I sat with the old banyan, a thought crossed my mind. A time will come, any sooner, when Faisalabad will divorce Lyallpur. It will disconnect itself from Bhagat Singh and conveniently choose to forget Sundar Singh Lyallpuri. The time will come when a child will stand around the Rail Bazar Gumti and ask his father “Who was James Broadwood Lyall?”.

“Why is this arched gate called Qaisari Darwaza?”

Unfortunately, the father will not have any answer, for he, too, was born in Faisalabad and not Lyallpur.

I was struck with the thought that slowly and gradually everything will be lost, but then, does it really matter. Except few historical cities (and that too for commercial purposes), every city has changed. Life moves on . . . and so shall the train.

When night grows dark, the old streets of Sanat pura and Grunanak pura transmit some Morris Code. These are the SOS messages from a sinking ship which can only be deciphered by the wind that blows over the canal.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment